Before I regale you with stories involving water buffalo, motorcycles, Indian weddings, and Indian bodybuilders (though not necessarily in that order), allow me to explain how I came to this point in my life.

My first memory of the idea of “India” (for that is all it was or could be at that point) came from seeing a National Geographic special as a kid, when I was 7 or 8, and having had an adult explain why there were cows roaming freely in the city streets. I remember at the time (I was living on a small “farm” in Southeast England) thinking that this country must have been a pretty unbelievable and messy place. This initial introduction was soon followed by an invitation to the house of an Indian Cub Scout friend of mine. I remember how upon entering his house the sensory experience completely overwhelmed me: the spicy aromas coming from the kitchen, the intense red and gold color of his mother’s sari and the fact that I was served blue rice which I think, in the end, I refused to eat with the obstinacy that young, picky British children have perfected. I have since confirmed that serving blue rice may have, in fact, been a peculiarity unique to this particular family, but for many subsequent years I associated this unnaturally colored food with Indians and India.

Fast forward to hearing the sitar in Beatles songs, revisiting Indian food, an Indian girlfriend (by way of Guyana and Toronto, so a bit removed) and then hearing a speaker in my senior year in college describe a new kind of development called Microfinance: giving small loans to groups of women so that they could better their lives through entrepreneurial efforts such as buying additional cows in order to sell more milk or even by purchasing a cell phone to rent it out on a per minute basis to neighboring villagers. This speech had quite an effect on me, since I was fortunate enough throughout my life to travel to developing countries like Belize, Jamaica, Mexico, and Cuba and wonder how you can help the people living by the side of the road under no more than tarps held up by thin tree branches. The idea of giving these people money and opportunity seemed incredible, especially if it actually succeeded in bringing them a better standard of living. But as is so often the case, the good ideas and intentions to get involved were pushed off the mental table by exams, rowing races, and preparing for graduate school.

Which brings me to my next wave of interest in India. Though this phase had a lot to do with writing my master’s dissertation on how September 11th had challenged and changed British Muslims’ sense of being British and being members of this fraught imagined community [and in the process of writing this poorly received piece of scholarly work (I needed a 60 to pass and I received a 61; odd considering that transpired so terribly a few years later) meeting with a number of Indians, Pakistanis, and Bangladeshis from casual conversations with my local corner shop owner, to the head of Zee TV’s news operations in London, to a member of the House of Lords] what really got me interested was my local curry house, Saffron Brasserie.

I realized early on in my time at Cambridge that I was an intellectual small fish in a very large pond. So, my remedy was to become a more social fish. I befriended the owner-operator of the Saffron Brasserie and as my cadre of International Relations and rowing friends grew, I organized increasingly large dinners, culminating with a group of at least 20 and a bill that came close to 500 pounds. Add on to that an American-sized tip and I had popadoms and a Cobra beer on the house each time I went in. Though the food was good, it was their great hospitality, friendliness and all of the places in India they enthusiastically told me I had to visit that led me to think I should spend some time here.

These personal experiences were further bolstered by all of the press India was receiving from Thomas Friedman and others in regards to the software and call centre boom. So I decided upon completing my masters course that I would try and get a job in India to bolster my international relations background and to see first hand the economic and social development taking place. The only snag was that I did not have any idea of what I could do there. I wrote e-mails to U.S. companies like Merrill Lynch because I read an incredulous article in the Boston Metro that the firm had just opened yet more Indian operations, employing financial analysts at $15,000 salary. These e-mails, not unexpectedly, went unanswered. Then very unexpectedly, I did get a response from Simon Long, the Economist’s Indian bureau chief. I had written just before the 2004 Indian elections, so he was very busy and as a result quite brief, but he encouraged me to figure out what I brought to the table for any firm who would hire me. In the end I realized that having no real professional experience made it difficult to get a job in Boston, where I was living, let alone half a world away. So, after 8 months of coaching crew as a professional stop gap, I finally joined a Boston-based consulting firm and embarked upon the task of acquiring professional skills to bring to the table. Moving to India was crowded off the table by my efforts to understand the “collision chamber” (as my firm branded their position) in which I had found myself between the telecom, digital media, and technology industries. This work took me to Japan for a few months with some great week long stopovers in London where I reconnected with one of my best friends from Cambridge, Leo. Leo and I had talked about planning another trip (we had a hilarious, pitfall-laden jaunt to Portugal after finishing our studies) and India was the prime target.

So I returned to the idea of moving to India because I was coming up on two years in consulting and would now have a chance to see if I could literally stomach living in India by having it take me for a test drive for two weeks in February of this year. I wrote up that trip, so I’ll spare the same audience the same material, but suffice it to say that I had a great time and was moving ever closer to finally getting over to India. The only thing to figure out was what exactly I wanted to do. So when I got back to the US I kept talking to the NGOs I’d met with in Mumbai and I also sought out some other possible options. After numerous discussions with friends and family who helped me realize that I wanted to help people by applying my fledging understanding of business, I returned to the idea of microfinance. Around this time, it was announced that Pierre and Pam Omidyar (the founders of eBay) had given Tufts University (our mutual alma mater) $100 million on the contingency that the money had to be invested in various microfinance projects around the world. After discussing all of this with a particularly supportive colleague he prompted me to call Tufts and see whether any of this money was bound for India and if so to whom. I called various administrative offices and eventually spoke with the individual responsible for administering the fund.

I explained my interest in working in India and professional background and he told me that just that week they had concluded meetings for the initial round of $5 million and one of the people who presented was Vikram Akula, founder and CEO of SKS Microfinance and a fellow graduate of Tufts. Thinking that I was now set “how could a fellow Tufts grad not want to hire me with my new skills that I brought to the table and a willingness to make a subsistence wage and drop all friends and family to move to India?” So with brimming expectations I e-mailed Vikram and waited…and waited. Until I got this response:

Chris,

Thank you for your email. While I appreciate your interest in SKS, we unfortunately are no longer recruiting non-local staff. I am copying Chris Turillio on this email, nevertheless, as he was in a similar position not too long ago and he can help you explore other options.

Best Regards,

Vikram Akula

________________________________________________

Founder and CEO | SKS Microfinance – Empowering the Poor

I e-mailed Chris Turillo crestfallen (both because landing a position wouldn’t be as easy as I had hoped and because here was another white-American-male who had already come up with this idea and acted on it). He was tremendously helpful, explaining how he had come to SKS and that, given my consulting background, I should look into a firm called Intellecap that specialized in consulting to the microfinance and social investment community. Not to be deterred, I called Intellecap and we set up a time to interview.

Now, before I continue, let me explain how life has a funny way of helping you along at times. On a Friday, about three weeks after I got back from India, as I’m sitting at my desk in New York enjoying my breakfast, I get a call from one of my mentors in Boston which goes a bit like this:

“Chris, I hired you so I felt I had to tell you this. The firm, as you know, is up for sale, let’s admit it, in a distressed manner, and there are some changes in the works. Chiefly, the New York office is being stripped and you and five others [there were only 9 people in the office] are being let go at the end of the day. Raul, [the CEO] is driving down from Boston right now. I’m sorry, and for what it is worth, they are making a huge mistake.”

I sort of lost grasp of reality for a few seconds. Utterly confused, I had just been promoted 9-months before from the entry level “Associate” to the MBA-level “Consultant”, I soon turned furious. I’d given a lot to the firm and couldn’t believe that they were tossing me aside.

The fury couldn’t last because about 20 minutes later, after making sure this was actually happening (not receiving the company-wide, end of the day meeting reminder e-mail is always a good sign that you are being terminated, severed, let-go, and fired), I turned contemplative: “Ok, not a problem, I’ve saved some money, and nothing will ensure that I actually follow through with this plan to go to India than being released from the ‘golden-handcuffs.’” Realizing that the other people who had been let go have children’s tuition, mortgage, and car payments also made me swallow my anger, since, for me, this was a minor inconvenience that would build character, and for them this was a significant professional and financial blow. Incidentally, the entire US operations went belly up three weeks later, so the check was in the mail no matter what.

So back to the interview with Intellecap. I sat there at 2:30 AM EST and began my first telephone-only interview with the two consulting team leaders, Anurag and Shree. Between the late hour, poor telephone connection, and the Indian-accented English, I had a hard time hearing the questions about how I would help their operations and why I had been with several companies in a relatively short period of time. We discussed the importance of profit seeking to transparency and accountability in the development sector as well as more prosaic topics like whether I would be willing to be paid an Indian salary. I found them to be extremely professional, engaging, and they described a company that was equally focused on helping the poor as it was to applying rigorous management and strategy expertise within the development sector.

Two weeks later I received an offer letter and after some initial waffling (the idea of being in Mumbai appealed to me; especially since one Indian colleague of mine compared Hyderabad and Mumbai to being the Cleveland and New York of India) and great conversations with three current employees, I accepted their offer. I was finally headed to work in India.

Several hard goodbyes to people in New York, seven boxes shipped to California, one Indian employment visa, one roundtrip ticket from San Francisco to Hyderabad, one week at home and two large, fully stuffed suitcases later I was on my way.

Though I left home at 14 to attend boarding school 400 miles away, this departure felt far more raw for all concerned. This had a lot to do with the distance (add 14,600 miles as the planes flew) and the unknown for all concerned. It was hard for me to imagine what I was about to experience and, I imagine, even more difficult for my parents who had last been in India in the late seventies. I saw my Mom wave me off with more than a few tears as my Dad stood next to her with his arm around her. The only slightly awkward part was that I was in the security line which wrapped around itself five or six times and all parties stood there until I went through the metal detector some 10 minutes after entering the line.

The flight was absolutely grueling. From San Francisco to Frankfurt there were bottles of Warsteiner rolling around the floor of the Lufthansa 747, while the pilot interrupted periodically over the PA system to update the passengers on the latest World Cup scores. From Frankfurt to Mumbai Lufthansa changed tack with Bollywood movies seemingly on loop throughout the flight. Due to the somewhat prudent use of Tylenol PM, the second flight was experienced in that uncomfortable state of semi-permanent drowsiness where your head falls forward and your autonomic response jerks it back upright. Once the plane landed in Mumbai (at 1:30 in the morning local time) things progressed more smoothly than I had even hoped. Rolling my two oversized suitcases through the International airport, I managed to clear immigration (“You are living in India, sir?” the immigration official said with raised eyebrows) and customs without incident and I even found my way to the Domestic terminal. Though it was by now two in the morning, the first wave of hot, sticky, humid air baptized me to the world of perpetual sweatiness this adventure would bestow upon me.

The fluorescent-bright white and steel domestic terminal was in stark contrast to the passengers who all sat sleeping in a line of oversized chairs at the back of the building. The security guards stood around glassy eyed and seemed to only manage to stay awake by craning their heads to watch the world cup on brand new flat-panel televisions that were oddly installed at about the height of a basketball rim. Having initially felt that the security was pretty lax, I was then patted down three times on my way to the plane. Once seated, I made the casual observation that I was the only Anglo, but I noted to myself that this is probably a funny thing to remark upon given that this will be the situation far more often than not. Again a steady stream of head nodding and snapping and intermittent interruptions from the apologetic flight attendant pleading for me to enjoy a drink or a snack. The flight from Mumbai to Hyderabad is only an hour, but the nascent privatized domestic airline market is the opposite of that in the US: they cram frills into every minute of the flight. At one point I even saw the hostess lean over three rows of seats to wake a passenger up to “enjoy” his complimentary orange juice.

When I landed I braced myself for the eventuality that the driver that Intellecap had arranged would not be at the arrivals gate. However, I have to say that I was not too worried since in my interactions with Indians they have been exactly where they said they would be at the exact time they had promised. So I wander dazed (it has now been 36 hours of travel) through the domestic exit and strain my eyes to see the placards being held up in the dim 4:30 AM light: “Gupta”, “Ghandi”, “Agrawal”…alas no “Mitchell”. At this point the taxi-wallahs smell fear and I am approached by a few who say “to town 600 rupees (about $13). Just as I was beginning to pick my opening bargaining number I see in the distance, about 40 feet ahead, a much larger group of people and many, many more placards—the international arrivals group. It dawns on me that if I were picking up an American that is likely where I would stand, so I pull my bags the 40 feet and enter the line. As I get to the middle of the line of the expectant mass, I see it: “Mr. Chriis MITcheLL.” I point to him and then point to myself and he runs around the railing and takes my bags.

He then starts at quite a clip for his car and I trot to match his pace. As we walk out of the terminal I notice some of the requisite sites of India: people sleeping on the sidewalk (at this point I thought it looked like a pretty good idea), stray dogs milling about, the old 1950s taxis and of course the smells which, if you have not smelled them before, can only be described as an amazing mix of sweetness and stench. We get in his cab and I begin the fruitless effort of trying to get him to state the price of the ride before we get to the destination. He says it will be 500 rupees ($10) which seems high to me, but let’s be honest very few of the bargaining chips are in my corner. We drive along and I am kept up by the wind in my face and the fact that I know these sites will be around me for the next year or so. It is at that point that I simultaneously say to myself “you did it, you’re here, in India, with a job, starting a great adventure that will change your life” and “holy shit, I’m here in India and not planning to even have a respite for 6 months.” The magnitude of these thoughts is dulled by the site of the huge lake that sits in the middle of the city and a 40 foot tall Buddha statue that is lit with yellow lights from below.

When we arrive at the hotel at 4:50 am, the driver gets out my bags and heads for the door which is one of those articulating gates they have on service elevators…of course this one has a padlock on it. “No big deal I tell myself, I’m sure they will let me in, and if not I can sleep on the street, on top of my bags (seriously, at this point it would have been perfect). Of course, the driver bangs on the gate and I see the three sets of feet on the ground behind a small wall come to life. They roll up the bedding in the reception area and open the gate. They let me in, ask me to sign the register and take me up to my room (incidentally, the very one from which I am writing to you now).

It is perfect. Two beds, a brand new color TV, AC, two chairs and a low table, a dresser, and a toilet without a shower. This confuses me when I’m getting the initial tour in Telgu, of course, but I let it pass because I’m here and I’m about to get to sleep. The bag boy leaves with a hearty thanks and 20 rupees and I go into the toilet to figure out how I am going to shower. I notice that there is a hose with a water gun thing on the end (like you see go unused in numerous American kitchen sinks) between the toilet and the drain. There are also two faucets coming out of the wall at about a foot from the ground, one hot, one cold and below a bucket about half full with water and another small cup inside. I remember from Japan that this filling the bucket and using the cup to splash it around my body is the system that is in use here. I, however, want a shower after 36 hours of stewing in my own juices. So this is what I do: strip down, put on my flip flops, squat on the ground and take the hose-water-gun and start showering as best as I can. Now I want you to know that the idea had passed my mind that I was showering with what was likely used as some sort of bidet, but I tell myself that that is part of the experience. It does the trick, I feel refreshed (well, as refreshed as I can feel) and I lay down in bed with cool, air-conditioned air blowing over me.

I had promised myself that I would go to work around 9:30 to start on the right foot and make a good dedicated, impression. 9:00 rolled by and I could barely raise my wrist to see my watch. My eyelids felt like they were being pulled down by heavy lead weights and I fell back asleep. This happened every twenty minutes until 10:20 when I pried myself from sleeps warm embrace and headed for the office wearing as wrinkle free an outfit as possible.

The receptionist called an auto-wallah (this is a fantastic three wheeled, covered, moped taxi) and I jumped in. As we start bobbing and weaving through the morning traffic, I realize that this experience is quite a bit different from my first trip here in February. Chiefly, these experiences aren’t completely new: I knew to expect the hair-raising driving, the cornucopia of smells (good and awful), the omnipotent poverty, the stares and giggles from strangers. Nevertheless, it is great to be back in India and I’m excited to meet all of my colleagues for the first time.

My auto-wallah has no idea where my office is and eventually just motions for me to get out and points at a random building. I try and take it all in stride (after all it’s not like I’m trying to arrive on time). I walk around looking as much for a friendly, English-speaking, face as the actual address. Eventually, a man working in a convenience shop asks what I am looking for (I think he’d hoped to hear a coke and some chips) and I tell him the address. He says “around the corner, third house on the right.” Astounded, I thank him and walk towards No. 72 Avanti Nagar. I go through the gate, walk up two flights of stairs and knock on the door. It opens quickly and I see a group of people (the women in Saris, the men in slacks and button up shirts) in what I presume to be a meeting.

“Hello, I’m Chris.”

One of the women stands up and says “Hello, Chris, good to see you. I’m Shree”

“Shree, great to meet you”

“And you, this is Anurag, and Manju, and (insert Indian name I immediately forget)”

Then the only other white person in the room says “Hi, Chris, I’m Sara.” I had spoken with Sara before making my decision to join Intellecap, so quickly names and faces are being united.

Shree then suggests I sit in on their meeting, a debrief from a client meeting with an Indian NGO that is looking to set up an elderly-targeted Microfinance Institution (MFI) in some of the Tsunami affected areas of Tamil Nadu and Kerala. I sit dazed, but am excited to hear about the kind of work I will soon be doing. After the meeting Shree takes me into the next room (the current office is housed in a converted two bedroom apartment) and shows me to my desk. Sitting on top is a brand new laptop, “this is your desk and computer, and you will find the case in bottom right drawer. Why don’t you get your self set up, check e-mail and we’ll meet in half an hour to talk about the rest of the week”

The rest of the day was much like the first day at any professional services company anywhere in the world: reading evolving policy guidelines, meeting all the team members, and having a two hour meeting with the three team leads of the three business units: consulting, research and training, and knowledge management. Around seven, I must have shown how tired I was and they suggested I head back to the hotel. Another fantastic auto rickshaw ride, shower (this time accompanied by a three inch tarantula-like spider on the wall beside me) a dosa dinner (a huge, spicy, crepe-like thing filled with a spicy potato and onion mash) and I was fast asleep by 8 pm.

I awoke bolt upright at 4:30 am, and decided to turn on the TV. I managed to catch game 5 of the NBA finals (that Dwayne Wade is incredible) and by 6:00 I was organizing things in my room and listening to the rain, thunder, and amplified morning prayers. By 7:00 I called for another dosa and by 8:00 I was knocking on the office door (and waking up our intern from a business school in Singapore who is staying at the office for his last week with the firm).

Day two consisted of more meetings and more reading, and they’ve been very good to let me gradually get accustomed to everything. At 10:30 Sara told me that we should head to the Police Commissioners office (all foreigners who are planning on staying more than 180 days must register with the police within 14 days of arriving in India). We walk in; I get a heavy frisking, and then head up to the second floor where foreigners are “processed”. After waiting 15 minutes or so I am allowed to talk to one of the bureaucrats who says I have to fill out three forms, provide him with an additional 5 pieces of documentation, and passport sized photos—all in triplicate. As I leave I notice a pair of girls clutching the tell tale maroon passports from the UK looking quite dejected, I can only presume from not having literally crossed all of their “t's” and dotted all of their “i's”.

We return to the Intellecap office and I am just about ready to get cracking on reading several hundreds of pages on urban microfinance and micro-insurance reading, when Piya, (an Indian girl in the office who has been helping me do everything from find my way around to get passport photos to pointing out the best liquor stores) says “Chris the real estate broker is here.” I jump up and meet Sunil, a shortish and roundish man with a perpetual smile spreading between his bulbous cheeks.

Piya asks me “so how much do you want to spend on a place?”

“Anywhere from 7000 ($120) to 10,000 ($215)” I say, having been told that this is the going rate for two bedroom apartments in Hyderabad.

“And you said you wanted a two bedroom right” she confirms.

“Yeah, is that not enough?”

“No, that is plenty.”

With that I follow Sunil down the dark stairwell from our office and into the sweltering heat. When we get out of the building’s gate he jumps on his (rather petite) motorcycle. I think to myself, “how’s this going to work then?” He starts it up and motions for me to jump on the back.

I don’t hesitate. A mix of “when in Rome” and the tacit acceptance that the eighth of an inch of canvas on the auto rickshaws I take to and from work really isn’t providing me any more protection than if I was riding on the back of a motorcycle, braces me. As any guy who has been in this situation can likely attest, I tried to figure out if I should wrap my arms around his waist and lean over one should like in “Days of Thunder” or should I reach behind me and hold on to the small handle-like-thing. I opted for the handle-like-thing (not that there’s anything wrong with you if you’ve gone for the Days of Thunder hold) and we take off over speed bumps in the road and no road at all. As we get to the main street my knees are clutching the outside of his thighs with vice-like strength as he accelerates into oncoming traffic on the wrong (loosely defined) side of the road. A quick note on the side of the road issue: imagine depopulating the UK and dropping 60 million New York taxi cab drivers, without any reorientation as to which side of the road they should drive on, into the road system.

Sunil thankfully turns off the main road and on to a series of side streets. I’m now calm enough to notice the people on the side of the road staring at me both because I stand out and because I have a look of complete terror written across my face.

We arrive at a new building with a series of parking spots on the ground floor and an elevator in the middle. Getting off two floors later he knocks on an apartment door and a nervous women opens it a crack. They converse in either Telgu or Hindi (I hope to be able to tell them apart eventually), but I get the gist to be “No, you can’t come in because I’m by myself and there aren’t any male family members around.”

After she shuts the door Sunil says “no problem the apartment is the one just above.” We take the elevator up one floor (“if you’ve got it flaunt it”) and go out on a large roof deck to the side of the 4th floor apartment. He pulls back some laundry that is blowing in the wind and asks me to look inside. It looks great, from the slit in the window I can see through, but is filled with boxes. Just then two gentlemen from the next door apartment appear and say hello. Sunil proceeds to tell them what’s going on and the older of the two men insists that I come into his apartment to see the quality of the place, meet his family and have some tea and biscuits. They were lovely—son living in Philadelphia, lots of respect for America—so much so that he ends the meeting by saying “When you live here I will look after you—treat you just like my own son.” I’m flattered (or at least I certainly act flattered) but insist that I see at least one more apartment as I want to have a point for comparison.

Sunil suddenly stops speaking English and seems to tell my new surrogate father that there just aren’t that many places this good and at this price (Rs 7000 = $155). I look around the apartment at the marble floors, new ceiling fans, the western and Indian style toilets and decide to take it. The place is only a 5 minute auto rickshaw drive or 15 minute walk from work and my new neighbors were so friendly that it seems like a great fit. I have just started the great process of outsourcing my life: I’ve just reduced my rent 90%.

We triumphantly get back on his bike and roar through the traffic back to the office, where I am told that I’ve just set a new Intellecap record for finding an apartment. Some of the more senior people in the office ask Sunil if the place is convenient and in good repair and he seems to assuage their concern, even if I couldn’t. As I return to my desk, Anurag tells me that Sunil has been on the phone with the landlord and we need to go and meet him in order to secure the place. He then increases the anxiety by saying that places in Hyderabad have been rented within the hour, so we had better move.

The three of us get in to the back of an auto (the short form of auto rickshaw that I’ll be using from now on) and head for the area near the airport—about a 20 minute drive. On the way Sunil and Anurag converse in Hindi and intersperse some information about the local landmarks we are passing.

Anurag suggests that we stop at an ATM before we get there as nothing says I am series about taking a place like cash (this seems to be universal). I get out 21,000, about $460 (three months rent—the security deposit system also seems universal) and stuff it into my back pocket. He then says “don’t show the money until its time” which confuses me because he doesn’t specify when “the time” is, but I just figure he’ll take care of that.

The landlord’s help shuffles to the door and after being urged to sit in the living room the landlord shuffles in like we’ve just woken him from a nap. He and Anurag discuss my candidacy in English—odd because I’m sitting right there and have a reasonable command of the language. Once he’s satisfied that Intellecap is a real business, he calls for his wife who appears in a beautiful red and gold sari. She sits down and takes over the conversation with Anurag:

“Now, we don’t want and of that American party and drinking action going on.”

Anurag responds, “No, Aunty (a generic term of deference for female elders) he has been to top schools and is very professional.”

I just sit there nervously, wondering if this means I can’t drink in my apartment.

“Ok, because we have heard about that and we don’t want him (me) to disturb the other residence with his music and such.”

Anurag repeats his refrain.

“You will be responsible and respectful?” [Yay, I get to have some lines in this interaction]

“Yes, ma’am I will. I can assure you that I will be very respectful.”

She says that I can come back and sign the lease agreement and pay the deposit later, but then Anurag says motioning to me, “He has brought the money and is happy to make the transaction now.”

The wife looks at the husband who nods and she says “Tika [sic], we’ll do it now.” I then pull out the largest wad of bills I’ve ever held (at least in terms of the amount of paper if not the actual value) and proceed to count out 21,000 in 500s. A few moments later the landlord takes the money and puts it in his shirt pocket.

“If you wouldn’t mind” I say rather meekly “may I have some sort of note that explains that I have given you this money under the expectation that I will be living at this certain apartment for a period of up to 11 months [standard lease term]?”

“You don’t need that. We have trust” the Landlady says.

Anurag senses my developed world displeasure at the idea of having just given over 21,000 with nothing to show for it, so he diplomatically gets her to write out an ad hoc receipt.

I feel something I guess I would call accomplishment after the interaction and we all head back to the office.

Inevitably, my days have become more routine (or the little things just stop being quite as noteworthy):

- Wake up; call down to reception for a dosa from the adjoining restaurant.

- Go into the bathroom, shower using the faucet and small bucket provided (I’ve stopped using the bide hose)

- Eat the dosa.

- Brush my teeth using bottled water.

- Go down stairs, hand over the room key.

- Have a mutually unintelligible conversation with the man at reception (Incidentally, I think he is asking me if I’m checking out since there is no fixed period on how long I will stay at the hotel, but I can’t be sure. It’s either that or he’s asking me if I slept well and the answer to both is the same, so I just look confused and say “Auto-wallah” to request that someone flag down an auto rickshaw for me.)

- Get out on the street and meet the stares and glares.

- Hop into the auto, say “Basheerbagh, Avanti Nagar”

- The auto driver shakes his head from side to side (more on this confusing gesture later) and we take off.

- Along the way, we pass fruit and vegetable stands piled high with mangos, eggplants, onions, potatoes and anything else you can think of. We narrowly miss stray dogs, other cars, buses, and trucks as we rattle over speed bumps and through potholes.

- Eventually we get into the Avanti Nagar area and I try and steer him in the right direction, but he inevitably veers off and I just ask him to stop, pay him the 17 rupees ($0.37) and hop out. Again I’m greeted by stares and glares as I walk through the streets to the office.

- I get to work around 9:15 and am usually one of the first few people there since the day officially starts at 10:00

- Then I check e-mail, sometimes catching up with some late night people on the East coast by instant messenger.

- The hours before lunch usually involve catching up on all that reading I was mentioning earlier.

- Lunch involves ordering from a set number of menus (choices: Indian or Indian-Chinese—which is a great hybrid) and sending out our office helper, for lack of a better word, to pick up our food.

- At lunch we lay out newspaper on our glass-topped conference table and dig in to palak paneer and lamb briyani with roti, a huge thin pancake-like bread. Eating with your hands, you tear off some roti and fold it over a bit of food and stuff in your mouth. A great way to eat.

- After lunch I fight to keep my eyelids, made heavy from an upside down internal clock and too much rice, open.

- More reading, some meetings about ongoing projects and reviewing existing project presentations

- The day ends around 6:30 when inevitably one of my colleagues offers to take me out or have me join them for dinner. I oblige, though eating a hearty curry and rice by myself, watching the World Cup, and falling asleep by 9:00 has been a great option a few nights

- Turn off all the lights in my room, check the floor for skittering cock roaches (yes, one night a cock roach flew on to my chest and proceeded to spasm uncontrollably until it fell back to the floor)

- Fall asleep immediately…sort of.

I will give you a better sense of my actual work, what we are doing and how I am contributing once it starts in earnest, but to the end of my first week, they have been very good about letting me get acclimated to the material at my own speed.

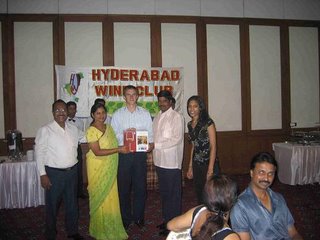

So, one of those nights where I joined a colleague, Anurag in this case, took me to one of the old colonial clubs, the Secudrabad Club, for a wedding reception. I didn’t know what to expect, since Indian weddings come with such a reputation, but what I found was something of an after party. After three consecutive days of partying, ceremonies and pomp, the bride and groom get to have a dinner with friends and family is a relatively relaxed setting. I added “relatively” because the bride and groom had to sit at the front of an audience of chairs receiving family members and friends for what I guess was at least an hour or two. We made our way up to the receiving area and Anurag introduced me as, “Chris, a new employee at Intellecap who has been in India for less than 48 hours.”

This impressed them I think (mostly that I was still awake at 10:30 pm). They were charming, he is working for Best Buy in Minneapolis and she is finishing working for a company in Hyderabad. In the course of our conversation I learn that they had met in person for the first time only 15 days before (not an arranged marriage—both parties consented fully—but one that the family and the internet facilitated) and that she was going to be joining him in Minneapolis.

Thanks to Emily I could speak somewhat knowledgably about Minneapolis and I tried to ease what I sensed to be a healthy dose of apprehension from the bride regarding moving to the US and Minneapolis winters (not that I’m a great expert on the latter).

We proceeded to meet the bride and groom’s family, take a few runs through the buffet line, enjoy some beers with an Indian guy with the best British accent; went to Bristol University and has returned to seek his fortune in the Bangalore real estate market.

By 11:30 I was losing the battle to fight off sleep, but we were told to stay because at midnight the bride would be turning 30 and they had a cake ready to surprise her. Two bottles of coke later we all gather around a table where the bride and groom feed each other and extended members of their family cake with their hands. The groom gets a piece in the face, and we all belt out a decent version of happy birthday. All fairly routine, until Anurag insists that the Bride, with whom he’d gone to business school, do her “famous” rendition of “I’m a little teapot.”

She protested repeatedly, but finally enough people started egging her on and she got in the middle of the circle and performed, what I have to say, was the best rendition I’ve ever seen. The bridal gown, henna painted hands and arms, and the fact that she was radiant had a lot to do with it.

Anurag noticed that I was increasingly slumped, so we said our good byes, I wished the Bride and Groom the best in the US and we hoped into a cab.

When I got home I noticed that the top of my tongue felt numb, while I did frantically worrying if this was one of the first signs of malaria, I’ve since decided that it is more likely that my taste buds are going on strike: “there is only so much consecutive spicy food we can take.”

I lay down and am out like a light.

As I get myself set up here I seem to be able to pretty much replicate the major aspects of my life in the US. This includes joining Hyderabad’s self proclaimed “Hottest gym for the coolest guys and gals,” Fitness World. My two American colleagues, Sara and Nilah, and one of our Indian coworkers, Piya, are all members so I went along to see what it was like.

Once I got there and they said I could join for $15 US a month I looked around the place (basically a square room that is 40 feet by 40 feet crammed full of all the usual apparatus) and signed up. I also immediately worked out that morning. I get to the locker room and am putting my things away when a tall, built Indian guy comes out of a near by stall and says,

“Hey, are you a player?” he says.

Not being sure how the term is being used, I look confused and ask “How do you mean?”

“You know, do you play?”

“Like sports, you mean?” I ask cautiously.

“Yeah, you look like you are fit, workout.”

“Yeah, I work out, thanks.” I say gingerly.

“Cool, I’m Rahul”

“Hi Rahul, I’m Chris, nice to meet you.”

“Krees, you are living in Hyderabad?”

“Yes, for at least a year.”

“Cool. See you later.”

I then continue to put my stuff away chuckling at the interaction. This would have been the most noteworthy thing that happened if I hadn’t met Sam, the gym’s resident trainer. When I got out to the gym in my shorts and T-shirt (no one is wearing shorts, by the way) I am met by the requisite stares and glares, so I head to the free weights. I stand in front of the stack and realize that the heaviest weights are a set of 45 lbs. Thinking maybe they are kilos I grab one and pull up easily. I do a set of shoulder press and then think that I should check out the machines since they will have to be heavier. I get over to the chest fly machine and put the pin in half way down the rack, put my arms in the right places and squeeze them together with a bang as the two sides collide. Thinking the pin must have slipped out; I check and put it at the very bottom of the stack. This time it’s a bit more difficult, but I do about 12 reps and at the end realize “Oh my god, I’m really strong here.” Just as I’m about to do another set of back exercises with the 45s, a fairly built Indian guy in a track suit comes over and introduces himself,

“Hi, I’m Sam, fitness trainer here, where are you from?”

“Sam, I’m Chris, I’m from California in the US.”

“Good to meet you. Let me show you how to do that”

Sam then proceeds to show me a much better technique while a crown of curios Indian guys gathers around.

“Ok, you do it like that.” Sam says.

“Great, thanks.”

So now I’m about to be lifting in front of an audience of eight to ten (which I have to say does increase performance). I do my best to mimic his actions and he looks on nodding his head, “Good boy, much better.”

I finish up my work out and head for the showers. While I’m undressing, Sam walks in. I say hello and he looks at me, cocks his head to one side and reaches out for my mid belly. “Here, around your lower abs, we can work on this fat area. And also your obliques are a little soft. Around the collarbone, your upper pecs, we have some work to do there, and your lower biceps and mid triceps need to be better in proportion.”

I stand there dumbfounded and Sam says “See you Monday, we’ll get started.”

At this point I feel a mixture of things but mostly that I’ve been admirably objectified.

----------------

Outbreak

One person in our office, Manju, has come down with what we suspect is Chikungunya, a non-fatal, mosquito-transmitted illness whose symptoms are sever fever and joint pain (sometimes lasting between 1 and 6 months after all other symptoms subside). There is no vaccine and no treatment beyond anti-inflammatory pills and rest. Initially this caused me significant panic as the gestation period is between 1 and 12 days between when you have been bitten and the symptoms manifest themselves. Since I’ve only been here 12 days, I feel that I could come down with it at any time. However, my panic subsided as I realized that since I am not taking anti-malarial pills, chikungunya would likely be preferable. In the end, the only solution for both of these is behavior that minimizes exposure to mosquitoes: using nets at night and DEET during the day. This is just part of tropical living and, unlike Delhi-belly, is not an affliction that targets the foreigner.

You will, of course, hear more about this if I have the displeasure of experiencing it first hand.

Loneliness

My acclimation to Hyderabad has been unbelievably smooth. All of the personal aspects, finding an apartment, getting a gas connection (not to be underrated), meeting a great group of people, have all sort of fallen into place. Professionally, the people are engaging and accepting and the work itself is exactly as I had hoped: it allows me to use and enhance my business skills in a socially conscious direction.

But there have been times when, just as I’m about to take yet another cold shower, I feel really far from “home.” Having moved around so much this concept is much less geographical or physical than it is psychological. At times I feel the loneliness in a more acute way. I’ve never lived by myself before, so that is part of it. But it is also the fact that I just look and act differently than almost everyone around me. Many of my American friends here are from Indian families, and even if they don’t speak Hindi, their skin and hair, if not their clothes, give them a degree of social camouflage from the stares and the glares.

But of it is also the fact that I left behind a four-year-on-and-off-again relationship which provided me with significant amounts of companionship, help and happiness. This facet of my life is in a determinably dormant state. Second guessing is to be expected.

So as I’m standing there trying to muster the will to take another cold shower, tightly holding my lips together for fear of having even a drop of this water enter my mouth and cause me dreaded Delhi-belly, it does get a bit much.

Yet, as I dry off and look out my window at the tops of the adjacent buildings, hear the vendors’ cries from the streets below, and maybe catch a lone cow wandering down the street, these thoughts seem to dull. They are especially put aside when my doorbell rings and I answer it to find the little girl from the family next door holding out a small cup of chai tea and biscuits her “Aunti” has asked to give me.

So there are lonely moments, and there is doubt, but these emotions have to fight with the present reality which is constantly assaulting the five senses. In the end, it seems like they just don’t have the strength to be heard over the cacophony.